By Reina Adriano

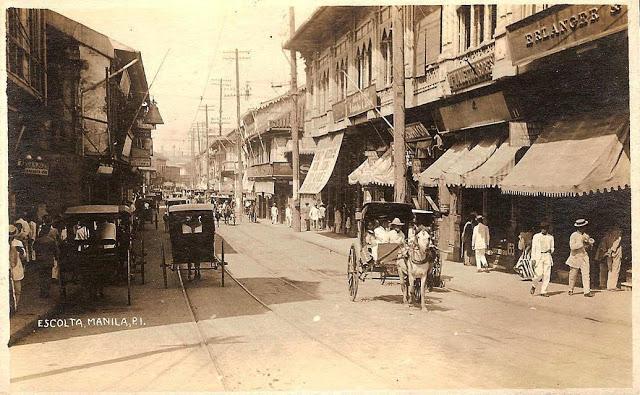

A postcard of Escolta, Manila during the World War II.

My penchant for history started with the books I grew up with, the ones I stashed deep in my suitcase filled with clothes and other belongings when I came to the States. I was (and still am) a bookworm who loved stories about my country’s roots from the Spanish, American, and Japanese occupations. They made me visualize the scenes that my social studies professors depicted in their lectures. In high school, I read martial law novels like Bamboo in the Wind by Azucena Grajo-Uranza, State of War by Ninotchka Rosca, and Empire of Memory by Eric Gamalinda. In college I had a penchant for historical accounts written for children with my favorite being Kung Bakit Umuulan by Rene Villanueva which depicted the Panayan legend of how the world was created.

When I came to the States, I realized that not everyone understood Philippine History the way I learned it. Many parents of first generation Filipino-Americans could not remember who were the heroes before World War II, much less tell their children stories of the Martial Law era. And even if they did try to scour for books about the Philippines, there is little explanation of the American occupation in the Philippines in textbooks, only that they staged a war to claim the country from Spain.

I invited friends to suggest some books to people in our BOSFilipinos community who are inclined to read about Philippine history, and many of them were eager to help. Buried histories contain a part of Filipino identity. They have the ability to explain why many Filipinos easily forgive and forget, why poverty remains in so many cities, and why we treat other nationalities the way that we do. Here is the compilation of those books, in hopes that people will find themselves intrigued at the depth of history that the Philippines has had over the years.

The Miseducation of the Filipino by Prof. Renato Constantino, Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1970)

“Although this set of readings aren’t necessarily Filipinx memoirs, etc., reading through them gives us a more objective perspective about the Filipinx-American culture and how it exists today. I think The Miseducation of the Filipino represents the essence of these readings pretty well: it talks about how the U.S. has used education as a means of ‘colonizing the minds’ of the Pilipinos during World War II. This education system is the foundation of the current Philippine education system that the remnants of American colonial teachings have now seeped through to our culture, giving birth to what most have called the ‘colonial mentality.’ As such, these readings aim to educate us about the colonial mentality that has persisted through generations and how we can use this knowledge to reclaim the true essence of the Pilipinx culture, independent of colonial influences. In the words of Samahang Pilipino at UCLA: Decolonize. Destigmatize. Educate. Empower!” - Recommended by Jaira Mendoza, intern at SPACE (Samahang Pilipino Advancing Community Empowerment)

The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata, Insurrecto, and Gun Dealers' Daughter by Gina Apostol

“My favorite is Raymundo Mata but Fil-Americans will totally relate to Insurrecto because it deals with identity. Insurrecto takes place in the present-day and tells the interweaving stories of Chiara, an American filmmaker and Magsalin, a Filipino translator. The two are forced to confront their past and question their identities as they embark on a journey to Samar together to work on a film about the Balangiga Massacre, a colonial atrocity committed by American soldiers in 1902. This intriguing and sardonic novel manages to capture the tensions of history and historiography and presents us the ways in which the shockwaves of colonial rule are still felt today.” - Recommended by Carmel Ilustrisimo, Creative Writing grad student at University of Santo Tomas

The Gods We Worship Live Next Door by Bino Realuyo

“This is a poetry book that is divided into different segments of Philippine history, following the Spanish, American, and Japanese occupations. Postcolonial as it may be, it shows us the diaspora of Filipinos during the tough times in those days, showing the effects of our colonization through a series of poems.” - Recommended by Angelo Galindo, Geography grad student at University of the Philippines

Slum as a Way of Life: A Study of Coping Behavior in an Urban Environment by F. Landa Jocano

“A saddening reality of Philippine society is the prevalence of slum communities. Jocano’s Slum as a Way of Life looks into how life in a slum community has affected the behavior of the people there. Although published in 1975, it remains a significant ethnographic study that puts into perspective the hardships and tribulations faced by these people who are, more often than not, looked upon with disdain by those higher in the social hierarchy. Concepts used are applicable even in today’s setting because although people may leave the slum area, the culture there is resistant to change. I believe that it is a work that should be read because it shows a different aspect to Filipino culture that is largely ignored. Aside from that, the method used by Jocano is simple and easy to understand focusing more on qualitative and descriptive approaches.” - Recommended by Nicole Poneles, BA Social Sciences graduate from UP Diliman

Pinatubo: The Volcano in Our Backyard by Robert Tantingco

“The book focuses and emphasizes one of the most talked about and internationally known calamities, the Pinatubo eruption. People knew about the demise some parts of the Philippines underwent, but people didn’t know what made some of those affected be resilient in those trying times. With a focus on the kapampangans, the readers will have a better and detailed glimpse on what other changes took place, be it into their lives, culture, and society. There are few genuine accounts of stories that are included to enrich the readers’ knowledge and understanding of the Mount Pinatubo eruption. his book also includes references and glimpses of mythology, science, and modern remembrance to make the whole account of the Mount Pinatubo eruption holistically known and understood.” - Recommended by Sig Yu, animation instructor

Barefoot in Fire by Barbara Ann Gamboa-Lewis

“It's about a Fil-Am girl growing up in World War II Manila. I remember it was a lot of daily life and the innocence of childhood, albeit with the war going on and attempts to understand the war from a child's perspective, limited as it is, seeing the humanity in everyone and seeing others as people and not just as sides in a war. Definitely stuff an adult would take with a grain of salt, but child readers, I think, will have a lot to think about. It's very vivid so you get a sense of what they ate while food was being rationed during WWII, how they used the bathroom, how they studied, among other things.” - Recommended by Stef Tran, poet

Breaking the Silence by Lourdes Montinola

“Montinola, the daughter of renowned doctor, Nicanor M. Reyes, founder of FEU, experimented with the process of searching and discovering the atrocities that happened to her family through many entry points, her memoirs of childhood. It was so gripping and emotional I read the book in one sitting! After the whole experience, I told myself, this should be read by all Filipinos to remind us never to relive that kind of war again brought about by colonialism! It's brutal. I recommend it to everyone who's interested in World War II memoirs.” - Recommended by John Toledo, grad student at UP Los Banos

The Summer Solstice and Other Stories by by Nick Joaquin

“Tatarin (the movie version of Nick Joaquin’s well-known story) fervently captures the belief of Filipinos in superstitions, deities, and religious practices weaved into communities and families. Also present in the narrative is the patriarchal ego that seeks to be stroked but a strong Filipina like Lupe Moreta counters the status quo in a traditional Filipino household by questioning her husband’s ideologies and encompassing the so-called limitations of a woman.” - Recommended by Reena Medina, University of Santo Tomas Teatro Tomasino alumna

America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan

”Bulosan’s memoir is about his childhood memories of immigrating to the States as a young boy from the Philippines. It depicts an immigrant’s journey as a laborer in the rural West trying to survive in a different country and culture, far from what he has been accustomed to back home.” - Recommended by Ludo Madrid

Feast and Famine by Rosario Cruz Lucero

“This book is a compilation stories about Negros Occidental that encompasses the entire Philippine history--from the Spanish occupation up until the Marcos era. Four stories and one novella are enough to tell the tale from a far-fetched province that felt the passage of time through the years.” - Recommended by Nicko de Guzman, assistant editor at Anvil

Seeing our heritage and the years of history embedded within the pages of books shapes our ideas of what the Philippines has become through the memories that continue to haunt us. And with those, a teeming desire to pass on what we know to people who are curious about our nation as well. My only request is that you pass on what you know about our nation’s history that many Filipinos try to discover but often fail to remember.

We’re always looking for BOSFilipinos blog writers! If you’d like to contribute, send us a note at info@bosfilipinos.com.